The US health care system is, unfortunately, extremely complicated to navigate. This results in disparities in care between patients, which causes many to suffer.

From the individual to the policy level, social workers serve as advocates to enhance care and make systemic change to improve outcomes. And in Associate Professor Dr. Rahbel Rahman-Tahir’s Health Care Policy and Advocacy course, Fordham Master of Social Work (MSW) students train to become real-world champions of patient equity.

This spring, the course’s final assignment asked students to:

- Propose a policy action plan at the community and/or legislative levels, including the development and implementation of a specific advocacy tool to address the identified policy issue

- Identify the stakeholders with whom to collaborate to execute the plan

- Address issues of affordability, accessibility, quality/acceptability, and availability

“It was an absolute honor teaching such a passionate and driven group of future health care changemakers. Their work went beyond academic expectations,” Rahman said. “The students transformed statistics into human stories by sharing personal and frontline experiences that revealed health care disparities in ways no textbook could. These projects were far more than assignments; they were testaments to the power of lived experience in making complex issues accessible, compelling, and impossible to ignore!”

We interviewed a few students from the class about their projects, including why this was a passion area for them and how the course prepared them to become effective social workers.

Bethany Cohen: Visualizing the Recovery Journey

For Bethany Cohen, painting was just a hobby she did for fun. She didn’t realize her art could become advocacy.

“Professor Raman had Professor Rogerio M. Pinto do a presentation for an art-based approach for advocacy,” Cohen said. “I wanted to do my own, so I did [a]mixed media [approach]of painting and drawing, combined.”

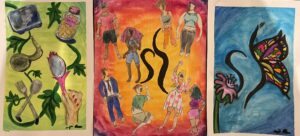

Cohen’s three-part painting series narrates the complex journey of eating disorder recovery. Each canvas represents a distinct phase: the darkness of illness, the struggle of treatment, and the hope of healing.

Cohen’s painting

The opening piece confronts the raw reality of eating disorders: weight fixation, low self-esteem, and negative relations with food. The second painting portrays the diversity of those affected, employing shadowing techniques to acknowledge recovery’s ongoing, non-linear nature. The final canvas, a butterfly inspired by the National Eating Disorder Association’s heart symbol, radiates themes of freedom and hope.

“Patients with eating disorders are underrepresented and overlooked, and I thought [the paintings]would be good to bring awareness to the public,” Cohen said.

Bethany Cohen. Photo courtesy of Bethany Cohen.

Cohen was the only student in class to pursue painting as advocacy, and said that Rahman’s embrace of creative approaches nurtured her willingness to share such personal work.

“She taught us that advocacy can look like a lot of different things,” Cohen said. “I was extremely intimidated by [policy work], but [Rahman] made it really accessible, digestible, and understandable.”

Even after graduating in May, Cohen’s impact remains at GSS. Her paintings will find permanent residence in GSS’s student lounge, accompanied by descriptions of each piece.

“I’m really grateful to the professors for giving me a voice to share my passion, and really encouraging that environment,” Cohen said. “My classmates were really supportive, too. I was really nervous about showing this, because it’s vulnerable to put your art on display. They were super encouraging.”

Eleanor Smith: Exposing Medicare’s Hidden Inequities

Drawing from her clinical experience as a Fordham GSS Palliative Care Fellow, Eleanor Smith wrote an op-ed examining the limitations of Medicare Advantage plans in end-of-life care settings. The inspiration behind the piece emerged from countless difficult conversations during her internship with families facing systemic barriers to appropriate care.

“It can be heartbreaking,” Smith said. “They can have an option that’s great for them: it’s close to home or would provide the best level of care, but we have to tell them that’s not available because their insurance plan won’t approve it for whatever reason.”

Eleanor Smith

Smith’s article raises awareness around the lack of education concerning these plans’ limitations. For example, patients are attracted to the plans’ promises of free dental and vision, only to face a harsh reality when those provisions don’t cover the specialized care that person needs, or the necessary treatment that is covered is slowed down by bureaucratic inefficiencies.

Additionally, Smith highlighted that these programs often target enrollment of vulnerable populations, particularly low-income individuals and marginalized groups. Unaware of the different plans’ intricacies, these people are then enrolled in lower-quality programs, compounding the negative systemic inequities they already face in daily life.

Like Cohen, Smith said she hadn’t considered the medium she chose as a form of advocacy until Rahman introduced the idea.

“When we think of advocacy or advocates, we think of really big-scale work,” Smith said. “Reframing advocacy and acknowledging that raising awareness is also an advocacy tool is an important first step.”

Overall, the project bridged Smith’s immediate clinical experiences with her long-term professional aspirations. After graduating in May, Smith plans to work in hospital social work, hoping to enter palliative care. This experience reminded her that these situations and conversations are not always easy, but they are necessary.

“Care often involves many heartbreaking conversations, but this one’s especially difficult because it feels like there’s something we should be able to do in this situation,” Smith said. “The purpose of my article was to raise awareness that this is something to consider.”

Alice Phan: Digital Advocacy for Mothers’ Postpartum Rights

Fifty percent of births in the U.S. happen under Medicaid, Alice Phan discovered during her research. However, health care for those enrolled in Medicaid is only covered for 60 days postpartum. Phan said this is not nearly enough time, especially considering that many mental health symptoms post-birth may not appear for up to a year.

“These people are undiagnosed for a year, and then a lot of them don’t have health insurance [after they are diagnosed],” Phan said.

For her advocacy tool, Phan designed a website to raise awareness for maternal mental health and Medicaid access expansion for mothers. A mother herself, Phan said this project hit home.

“Society expects you to go back to work within six weeks [of giving birth],” she said. “They say, ‘You’re a normal human.’ That’s not the case.”

Phan, like many state advocates, thinks Medicaid should allow access to health care at least one year postpartum. Similarly to other health care disparities, Phan said this issue compounds and impacts vulnerable populations the most.

“A lot of times, women carry the burden of childcare, housework, financial stress—and a lot of times they’re coming from low-income or different socioeconomic statuses and have less access to resources,” she said. “I’ve learned that it’s all a domino effect.”

In addition to being a mother, Phan also has firsthand experience in the health care industry. A former optometrist, Phan said she missed her connections with patients the most when the pandemic began. Her career pivot came from a desire to deepen those ties with others in scenarios apart from annual eye exams, and to have a bigger impact on broader policy change. She said this project was a good look into the future.

“I want to do more policy work, but I also want to see individual clients,” she said. “I would love to do both. That’s my ideal world.”

Lily Hammer: Defending Digital Access for Rural Communities and Older Adults

Lily Hammer’s project began with a concerning policy discussion in Rahman’s course. She and her class members learned that a proposed policy renewal involving telehealth, a service they’d all taken for granted in a post-COVID world, may be rejected and cause major accessibility issues for large swaths of people.

Lily Hammer. Photo courtesy of Lily Hammer.

Hammer is headed for a career in aging services, a sector that is growing more reliant on telehealth tools. This bolstered her passion for the subject.

“It was relevant to the populations I work with who receive Medicare and many older adults who have mobility issues or issues accessing transportation,” she said.

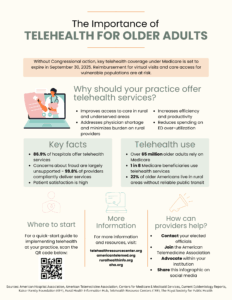

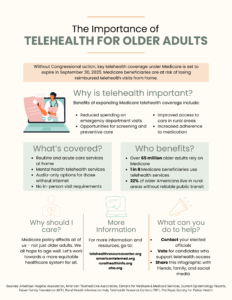

Hammer developed infographics designed for social media sharing and tailored for distinct audiences: the general public and health care professionals. Both versions communicated how COVID-era telehealth policy expansions had revolutionized health care access for rural older adults, who face geographic isolation, transportation barriers, and provider shortages.

Hammer’s tools served a dual purpose—to generate public awareness of the proposed policy, and to persuade health care professionals to implement telehealth in their practices.

- Hammer’s infographic for health care providers.

- Hammer’s infographic for the general public

The type of policy discussion that inspired Hammer’s project happened regularly, Hammer said. Each week, Rahman began class with a collaborative conversation on current events in health care policy. Hammer said the discussions helped fuse the theory she learned in class with real-world scenarios that would affect her clients after graduation.

Kara Mueller: Amplifying Voices of Young Adults with Disabilities

During her internship within a hospital’s Multiple Sclerosis Center, Kara Mueller identified a deeply troubling pattern: young adults with physical disabilities were being systematically channeled into nursing facilities designed for older populations. Sometimes, this inappropriate social setting would cause the younger adult to forego treatment altogether.

Mueller said young adults would choose to stay in a more uncomfortable situation with their parents or siblings, most of whom were not trained in how to properly care for disabilities, just to avoid the nursing home dynamics. This was a big problem.

“They fell through the cracks [within the nursing homes],” Mueller said. “They don’t have community; they struggle finding any sort of connections because the activities are more geared toward older adults.”

Mueller developed a comprehensive visual presentation targeting New Jersey legislators (her home state) that explained the issue and offered solutions. She proposed strategic Medicaid fund reallocation to strengthen long-term care facilities’ capacities to effectively provide services for younger adults with disabilities.

If her tool were to make it in front of future legislators, Mueller said, she thinks the subject would lend itself to Participatory Action Research (PAR), a method where researchers include those with lived experience in the subject matter to conduct the study. By allowing the younger adult population to conduct such a study, Muller said, the research’s impact would be even more profound.

“A more meaningful experience would be to get these patients and their families involved,” Mueller said.